Mérida, Yucatán

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Mérida | |

|---|---|

City | |

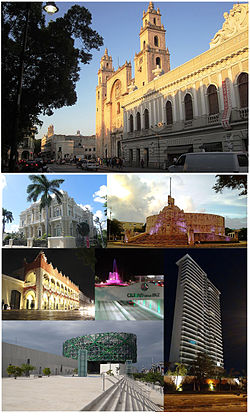

Above, from left to right: San Ildefonso Cathedral, the Canton Palace, the Monument to the Fatherland, the Municipal Palace, the Glorieta de la Paz, the Great Museum of the Maya World and a view of the Country Towers. | |

| Nickname: "La Ciudad Blanca" (The White City) | |

| Coordinates: 20°58′12″N 89°37′12″W / 20.97000°N 89.62000°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| State | Yucatán |

| Municipality | Mérida |

| City founded | January 6, 1542 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,201,000 (Metro) |

| • Rank | 34th in North America 12th in Mexico |

| Demonym | Meridiano |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $26.1 billion[2] |

| • Per capita | $21,400 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Postal code | 97000 |

| Area code | 999 |

| Major airport | Mérida International Airport |

| IATA Code | MID |

| ICAO Code | MMMD |

| INEGI Code | 310500001[3] |

| Climate | Aw |

Mérida (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈmeɾiða] , Yucatec Maya: Joꞌ)[4] is the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán, and the largest city in southeastern Mexico. The city is also the seat of the eponymous municipality. It is located slightly inland from the northwest corner of the Yucatán Peninsula, about 35 km (22 mi) inland from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. In 2020, it had a population of 921,770 while its metropolitan area, which also includes the cities of Kanasín and Umán, had a population of 1,316,090.[5]

Mérida is also the cultural and financial capital of the Yucatán Peninsula. The city's rich cultural heritage is a product of the syncretism of the Maya and Spanish cultures during the colonial era. The Cathedral of Mérida, Yucatán was built in the late 16th century with stones from nearby Maya ruins and is the oldest cathedral in the mainland Americas.[6] The city has the third largest old town district on the continent.[7] It was the first city to be named American Capital of Culture, and the only city that has received the title twice.[8]

Mérida is among the safest cities of Mexico as well as in the Americas.[9] In 2015, the city was certified as an International Safe Community by the Karolinska Institute of Sweden for its high level of public security.[10] Forbes has ranked Mérida three times as one of the three best cities in Mexico to live, invest and do business.[11] In 2022, the UN-Habitat's City Prosperity Index recognized Mérida as the city with the highest quality of life in Mexico.[12]

Nickname

[edit]

Mérida was named after Mérida, Spain because the Maya ruins that the Spanish conquistadors found in the settlement of Ti'ho reminded them of the Roman ruins of Augusta Emerita. Over time, the city acquired the nickname "La Ciudad Blanca" (The White City).[citation needed] This nickname may be due to the white color of the limestone used to paint the façades of the city's colonial buildings. This hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that the city can be seen from outer space as a large whitish area in the middle of the immense green forest that covers the Yucatán Peninsula.[13] Other cities in Hispanic America share the same nickname for this reason, like Arequipa[14] and Popayan.[15] Folktale says that the name go back to the founding of the city when the Spanish conquistadors – motivated by security reasons and given the persistent rebellion of the indigenous Maya people – decided to allow only white-skinned Europeans to live in the city. Old arches at the entrance to the city would have been built for this reason, and beyond these were the Indian communities.[16] However, the first arches were not commissioned until 1690, almost 150 years after the city's foundation. The arch of San Juan and the one on 59th street marked the beginning of roads to Campeche and Izamal, respectively. Other arches served only decorative purposes, like the one Juan Quijano had erected in 1760 in front of his house at the intersection of 65th and 56th streets, which has since been demolished.[17] Additionally, the Nahua indigenous troops who accompanied Montejo's troops in the conquest of Yucatán settled in the neighborhoods of San Cristóbal, Santiago, and San Román, where they enjoyed the privilege of exemption from taxes for their military assistance.[18]

History

[edit]

Mérida was founded in 1542 by the Spanish conquistadors, including Francisco de Montejo the Younger and Juan de la Cámara, and named after the town of Mérida in Extremadura, Spain. It was built on the site of the Maya city of Ti'ho (/tʼχoʼ/), which was also called Ichkanzihóo or Ichcaanzihó (/iʃkan'siχo/; "City of Five Hills") in reference to its pyramids. Many of the carved stones of the ruins of ancient Ti'ho were used in the construction of the early Spanish buildings of Mérida. These stones are visible, for instance, in the walls of the main cathedral. From colonial times through the mid-19th century, Mérida was a walled city designed to protect the peninsulares and criollos from periodic revolts by the indigenous Maya people.

In the late 19th century, the area surrounding Mérida prospered from the cultivation of henequen, the fiber of which was used in the production of rope and twine, as well as for the production of licor del henequén, a traditional Mexican alcoholic drink. By the beginning of the 20th century, manufacturing focused mainly on tobacco, molasses, rum, soap, and leather products.[19] Korean immigration to Mexico began in 1905 when more than a thousand people arrived in Yucatán from the city of Jemulpo. These first Korean immigrants settled around Mérida as workers in henequen plantations.

In August 1993, Pope John Paul II visited the city on his third trip to Mexico.[20] The city has been host to two bilateral United States – Mexico conferences, the first in 1999 (Bill Clinton – Ernesto Zedillo) and the second in 2007 (George W. Bush – Felipe Calderón, which resulted in the creation of the Mérida Initiative). Mérida hosted the VI Summit of Association of Caribbean States in April 2014. In recent years, important sports competitions have been held in Mérida, such as the World Cup of the World Archery Federation. The city has also hosted important scientific meetings such as the International Cosmic Ray Conference.

Geography

[edit]Mérida is located in the northwest part of the state of Yucatán, which occupies the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. To the north is Progreso and the Gulf of Mexico. Valladolid and Tizimín are to the east, Celestún is to the west, and the city of Campeche is located to the southwest. There are many important Maya archae sites in the area, including Chichen Itza, Uxmal, Oxkintok, Sayil and Kabah.

The city is located near the center of the Chicxulub Crater. It has a very flat topography and is only 9 metres (30 ft) above sea level. The land outside of Mérida is covered with smaller scrub trees and former henequen fields. Almost no surface water exists, but several cenotes (sinkholes that provide access to underground springs and rivers) are found in the area.

Mérida has a centro histórico typical of colonial Spanish cities. The street grid is based on odd-numbered streets running east–west and even-numbered streets running north–south, with Calles 60 and 61 bounding the "Plaza Grande" in the heart of the city. The more affluent neighborhoods are located to the north and the most densely populated areas are to the south.

Climate

[edit]Mérida features a tropical savanna climate (Köppen: Aw).[21] The city lies in the trade wind belt close to the Tropic of Cancer, with the prevailing wind from the east. Mérida's climate is hot and its humidity is moderate to high, depending on the time of year. The average annual high temperature is 33.5 °C (92.3 °F), ranging from 30.6 °C (87.1 °F) in December to 36.3 °C (97.3 °F) in May, but temperatures often rise above 38 °C (100.4 °F) in the afternoon during this period. Low temperatures range between 17.2 °C (63.0 °F) in January to 21.7 °C (71.1 °F) in May. It is most often a few degrees hotter in Mérida than in coastal areas due to its inland location and low elevation. The rainy season runs from June through October, associated with the Mexican monsoon which draws warm, moist air landward. Easterly waves and tropical storms also affect the area during this season.

| Climate data for Mérida (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.5 (103.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

42.0 (107.6) |

43.0 (109.4) |

44.2 (111.6) |

42.0 (107.6) |

40.0 (104.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

40.0 (104.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

44.2 (111.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.8 (87.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.9 (94.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 38.4 (1.51) |

32.2 (1.27) |

22.5 (0.89) |

24.4 (0.96) |

69.4 (2.73) |

138.3 (5.44) |

158.7 (6.25) |

140.7 (5.54) |

183.1 (7.21) |

127.9 (5.04) |

56.2 (2.21) |

45.1 (1.78) |

1,036.9 (40.82) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 13.4 | 12.8 | 13.9 | 9.7 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 86.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 68 | 63 | 64 | 63 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 76 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 208.6 | 205.9 | 241.8 | 254.1 | 273.2 | 231.0 | 246.1 | 247.9 | 208.5 | 218.5 | 212.4 | 201.8 | 2,749.8 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorologico Nacional (humidity 1981–2000)[22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[24] | |||||||||||||

Governance

[edit]

Mérida is the capital of the state of Yucatán. The offices of the governor of Yucatán, the Congress of Yucatán, and the Superior Court of Justice of Yucatán are all located within the city.

The municipal government is invested under the authority of a City Council (Ayuntamiento) which it is seated at the Municipal Palace of Merida, located in the historic center of the city. The City Council is presided by a municipal president or mayor, and an assembly conformed by a number of regents (regidores) and trustees (síndicos). Renán Barrera Concha became Mayor on September 1, 2018.

Economy

[edit]

The Yucatán Peninsula, in particular the capital city Mérida, is in a prime location which allows for economic growth. Mérida has been a popular location for investment.[25] This, in turn, has allowed the Yucatán economy to grow at three times the rate of the national average.[25]

In addition, the World Bank Group's Ease of Doing Business Index ranked Mérida fourth nationally in the category of ease of starting a business.[26]

Science and technology

[edit]

The city is home to important national and local research institutes, like the Yucatan Scientific Research Center (Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, CICY) of the National Council of Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Conacyt), a unit of the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados, CINVESTAV Unidad Mérida), the Dr. Hideyo Noguchi Regional Research Center (Centro de Investigaciones Regionales Dr. Hideyo Noguchi) of the Autonomous University of Yucatan (CIR-UADY), the Yucatán Science and Technology Park (Parque Científico Tecnológico de Yucatán, PCYTY) and the Peninsular Center for Humanities and Social Sciences (Centro Peninsular en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, CEPHCIS) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Culture

[edit]

Mérida has served as the American Capital of Culture in the years 2000 and 2017.[27]

As the state and regional capital, Mérida is a cultural center, featuring multiple museums, art galleries, restaurants, movie theatres, and shops. Mérida retains an abundance of colonial buildings and is a cultural center with music and dancing playing an important part in day-to-day life. At the same time it is a modern city with a range of shopping malls, auto dealerships, hotels, restaurants, and leisure facilities. The famous avenue Paseo de Montejo is lined with original sculpture. Each year, the MACAY Museum in Mérida mounts a new sculpture installation, featuring works from Mexico and one other chosen country. Each exhibit remains for 10 months of the year. In 2007, sculptures on Paseo de Montejo featured works by artists from Mexico and Japan.

Mérida and the state of Yucatán have traditionally been isolated from the rest of the country by geography, creating a unique culture. The conquistadors found the Maya culture to be incredibly resilient, and their attempts to eradicate Maya tradition, religion, and culture had only moderate success. The surviving remnants of the Maya culture can be seen every day, in speech, dress, and in both written and oral histories. It is especially apparent in holidays like Hanal Pixan, a Maya/Catholic Day of the Dead celebration. It falls on November 1 and 2 (one day for adults, and one for children) and is commemorated by elaborate altars dedicated to dead relatives. It is a compromise between the two religions with crucifixes mingled with skull decorations and food sacrifices/offerings. Múkbil pollo (pronounced/'mykβil pʰoʎoˀ/) is the Maya tamal pie offered to the dead on All Saints' Day, traditionally accompanied by a cup of hot chocolate. Many Yucatecans enjoy eating this on and around the Day of the Dead. And, while complicated to make, they can be purchased and even shipped via air. (Muk-bil literally means "to put in the ground" or to cook in a pib, an underground oven).

For English speakers or would-be speakers, Mérida has the Mérida English Library,[28] a lending library with an extensive collection of English books, videos, tapes, and children's books. The library is also the site for expatriate meetings, children's storytelling hours, and other cultural events.

Mérida is also home to the Yucatán Symphony Orchestra, which plays regular seasons at the José Peón Contreras Theatre on Calle 60 and features classical music, jazz, and opera.[29]

Food

[edit]Yucatán food is its own unique style and is very different from what most people consider "Mexican" food. It includes influences from the local Maya cuisine, as well as Caribbean, Mexican, European and Middle Eastern foods. Tropical fruit, such as coconut, pineapple, plum, tamarind and mamey are often used in Yucatán cuisine.

There are many regional dishes. Some of them are:

- Poc Chuc, a Maya/Yucateco version of boiled/grilled pork

- Salbutes and Panuchos. Salbutes are soft, cooked tortillas with lettuce, tomato, turkey and avocado on top. Panuchos feature fried tortillas filled with black beans, and topped with turkey or chicken, lettuce, avocado and pickled onions. Habanero chiles accompany most dishes, either in solid or puréed form, along with fresh limes and corn tortillas.

- Queso Relleno is a gourmet dish featuring ground pork inside of a carved edam cheese ball served with tomato sauce

- Pavo en Relleno Negro (also known locally as Chimole) is turkey meat stew cooked with a black paste made from roasted chiles, a local version of the mole de guajalote found throughout Mexico. The meat soaked in the black soup is also served in tacos, sandwiches and even in panuchos or salbutes.

- Sopa de Lima is a lime soup with a chicken broth base often accompanied by shredded chicken or turkey and crispy tortilla.

- Papadzules, egg tacos bathed with pumpkin seed sauce and tomatoes.

- Cochinita pibil is a marinated pork dish, by far the most renowned from Yucatán, that is made with achiote. Achiote is a reddish spice with a distinctive flavor and peppery smell. It is also known by the Spanish (Recados) seasoning paste.

- Bul keken (Mayan for "beans and pork") is a traditional black bean and pork soup. The soup is served in the home on Mondays in most Yucatán towns. The soup is usually served with chopped onions, radishes, chiles, and tortillas. This dish is also commonly referred to as frijol con puerco.

- Brazo de reina (Spanish for "The Queen's Arm") is a traditional tamal dish. A long, flat tamal is topped with ground pumpkin seeds and rolled up like a roll cake. The long roll is then cut into slices. The slices are topped with a tomato sauce and a pumpkin seed garnish.

- Tamales colados is a traditional dish made with pork/chicken, banana leaf, fresh corn masa and achiote paste, seasoned with roasted tomato sauce.

Achiote is a popular spice in the area. It is derived from the hard annatto seed found in the region. The whole seed is ground together with other spices and formed into a reddish seasoning paste, called recado rojo. The other ingredients in the paste include cinnamon, allspice berries, cloves, Mexican oregano, cumin seed, sea salt, mild black peppercorns, apple cider vinegar, and garlic.

Hot sauce in Mérida is usually made from the indigenous chiles in the area which include: Chile Xcatik, Chile Seco de Yucatán, and Chile Habanero.

Language and accent

[edit]The Spanish language spoken in the Yucatán is readily identifiable as different in comparison to the Spanish spoken all over the country, and even to non-native ears. It is heavily influenced by the Yucatec Maya language, which is spoken by a third of the population of the State of Yucatán. The Mayan language is melodic, filled with ejective consonants (p', k', and t') and "sh" sounds (represented by the letter "x" in the Mayan language). Even though many people speak Mayan, there is much stigma associated with it. It can be seen that elders were associated with higher status with knowledge of the language, but the younger generation saw more negative attitudes with knowledge of the language[30] This was also in direct correlation with the socioeconomic status and their overall placement in society. There is also the idea that one is not speaking in the "correct" manner of legitimate Mayan dialect, which also causes for more differences in the accent and overall language of the area.[30]

Due to being enclosed by the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, and being somewhat isolated from the rest of Mexico, Yucatecan Spanish has also preserved many words that are no longer used in many other Spanish-speaking areas of the world. However, over the years with the improvement of transportation and technology with the presence of radio, internet, and TV, many elements of the culture and language of the rest of Mexico are now slowly but consistently permeating the culture.

Apart from the Mayan language, which is the mother-tongue of many Yucatecans, students now choose to learn a foreign language such as English, which is taught in most schools.

Main sights

[edit]Historic sites

[edit]

Modern Mérida has expanded far beyond its original city walls, but many old Spanish colonial buildings and several old city gates can still be seen in the centro histórico, which is among the largest in the Americas. Many large and elaborate homes from the early 20th century still line the main avenue called Paseo de Montejo. For example, "Las Casas Gemelas" (The Twin Houses) are two side-by-side French and Spanish style mansions completed in 1911 by Camilo and Ernesto Cámara Zavala. Owned by the Barbachano and Molina Méndez families, they are two of only a few houses that are still used as residences on Paseo Montejo from that era. During the Porfiriato, the Barbachano house held cultural events that hosted artists, poets, and writers. In the mid-1900s, the Barbachanos hosted aristocrats including Princess Grace and Prince Ranier, as well as first lady of the U.S., Jacqueline Kennedy.[31]

The historical center of Mérida is currently undergoing a renaissance, as people and businesses move into these old buildings and restore them.[32] Many of these restored buildings now serve as office buildings for banks and insurance companies. Other important historic sites in the city include:

- Antiguo convento de Nuestra Señora de la Consolación (Nuns)(1596)

- Barrio y Capilla de Santa Lucía (1575)

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial del antiguo pueblo de Itzimná

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial de San Cristóbal (1796)

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial de San Sebastián (1706)

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial de Santa Ana (1733)

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial de Santa Lucía (1575)

- Barrio y Templo Parroquial de Santiago (1637)

- Capilla de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (1706)

- Capilla y parque de San Juan Bautista (1552)

- Casa de Montejo (1549)

- Catedral de San Ildefonso (1598), first in continental América.

- Iglesia del Jesús o de la Tercera Orden (Third Order) (1618)

- Las Casas Gemelas aka The Twin Houses (1911)

- Monumento à la Patria (1956)

- Palacio de Gobierno (1892)

- Templo de San Juan de Dios (1562)

Cultural centers

[edit]- Centro Cultural Andrés Quintana Roo, in Santa Ana, with galleries and artistic events.

- Centro Cultural Olimpo. Next to the Municipal Palace in the Plaza Grande.

- Casa de la Cultura del Mayab, the Casa de Artesanías (house of handcrafts) resides there. It's in downtown Mérida.

- Centro Estatal de Bellas Artes (CEBA). Across the El Centenario, offers classes and education in painting, music, theater, ballet, jazz, folklore, dance, among others.

- Centro Cultural del Niño Yucateco (CECUNY) in Mejorada, in a 16th-century building, with classes and workshops specifically designed for kids.

- Centro Cultural Dante a private center within one of the major bookstores in Mérida (Librería Dante).

Museums

[edit]

- Gran Museo del Mundo Maya, Yucatán's Maya Museum, offers a view of Yucatán's history and identity.

- Museo de Antropología e Historia "Palacio Cantón", Yucatán's history and archaeology Museum.

- Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Ateneo de Yucatán (MACAY), in the heart of the city right next to the cathedral. Permanent and rotating pictorial expositions.

- Museo de la Canción Yucateca Asociación Civil in Mejorada, honors the trova yucateca authors, Ricardo Palmerín, Guty Cárdenas, Juan Acereto, Pastor Cervera y Luis Espinosa Alcalá.

- Museum of the City of Merida, relocated to the old Correos (post office) building in 2007, houses important artifacts dating back to the Spanish colonial era as well as the Pre-Columbian era.

- Museo de Historia Natural, a natural history museum.

- Museo de Arte Popular, popular art museum, offers a view of popular artistry and handcrafts among ethnic Mexican groups and cultures.

- Museo Conmemorativo de la Inmigración Coreana a Yucatán.

Major theaters with regular shows

[edit]- Teatro José Peón Contreras

- Teatro Daniel Ayala Pérez

- Teatro Mérida (Now Teatro Armando Manzanero)

- Teatro Colón

- Teatro Universitario Felipe Carrillo Puerto

- Teatro Héctor Herrera

Sports

[edit]Several facilities can be found where to practice sports:

- Estadio Salvador Alvarado in the center

- Unidad Deportiva Kukulcán (with the major football Stadium Carlos Iturralde, Kukulcan BaseBall Park and Polifórum Zamná multipurpose arena)

- Complejo deportivo La Inalambrica, in the west (with archery facilities that held a world series championship )

- Unidad deportiva Benito Juarez Garcia, in the northeast.

- Gimnasio Polifuncional, where professional basketball team Mayas de Yucatán plays for the Liga Nacional de Baloncesto Profesional de México (LNBP) representing Yucatán.

| Team | Sport | League | Stadium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leones de Yucatán | Baseball | Mexican Baseball League | Parque Kukulkán |

| Venados F.C. | Football | Liga de Expansión MX | Estadio Carlos Iturralde |

The city is home to the Mérida Marathon, held each year since 1986.[33]

Transportation

[edit]Bus

[edit]

City service is mostly provided by four local transportation companies: Unión de Camioneros de Yucatán (UCY), Alianza de Camioneros de Yucatán (ACY), Rápidos de Mérida, and Minis 2000. Bus transportation is at the same level or better than that of bigger cities like Guadalajara or Mexico City. Climate-controlled buses and micro-buses (smaller in size) are not uncommon.

As of 2024 the privately owned city bus system is being replaced by a new municipal system called "Va y Ven".[34]

Ie-Tram Yucatán is a bus rapid transit (BRT) system opening in December 2023.[35]

The main bus terminal (CAME) offers first-class (ADO) and luxury services (ADO PLATINO, ADO GL) to most southern Mexico cities outside Yucatán with a fleet consisting of Mercedes Benz and Volvo buses. Shorter intrastate routes are serviced by many smaller terminals around the city, mainly in downtown.

Taxis

[edit]Several groups and unions offer taxi transportation: Frente Único de los Trabajadores del Volante (FUTV) (white taxis), Unión de Taxistas Independientes (UTI), and Radiotaxímetros de Yucatán, among others. Some of them offer metered service, but most work based on a flat rate depending on destination. Competition has made it of more common use than it was years ago.

Taxis can be either found at one of many predefined places around the city (Taxi de Sitio), waved down along the road, or called in by radio. Unlike the sophisticated RF counterparts in the US, a Civil Band radio is used and is equally effective. Usually a taxi will respond and arrive within 5 minutes.

Another type of taxi service is called "Colectivo". Colectivo taxis work like small buses on a predefined route and for a small fare. Usually accommodating 8 to 10 people.

Uber, DiDi, and inDrive also offer services in Mérida.

Air

[edit]

Mérida (IATA: MID, ICAO: MMMD) is serviced by Manuel Crescencio Rejón International Airport with daily non-stop services to major cities in Mexico including Mexico City, Monterrey, Villahermosa, Cancún, Guadalajara, Tuxtla Gutierrez, and Toluca. The airport has international flights to Miami, Houston, La Havana and Toronto. As of 2006[update] more than 1 million passengers were using this airport every year, (1.3 in 2007).[36] The airport is under ASUR administration.

Train

[edit]Mérida was the hub of an extensive narrow gauge railway network that operated in the states of Yucatán and Campeche beginning in 1902. This system was merged into Ferrocarriles Unidos del Sureste in 1975, and later merged into Ferrocarriles Chiapas-Mayab. In 2016, The Secretary of Communications and Transportation revoked the concession.[37]

Current passenger train service to Mérida is provided by Tren Maya which runs from Palenque, Chiapas to Cancún, Quintana Roo, continuing on to Playa del Carmen. It stops at Teya Mérida railway station, 8 km (5.0 mi) east of the city.[38]

Roads

[edit]Main roads in and out of Mérida:

- Mérida-Progreso (Federal 261), 33 kilometres (21 miles) long with 8 lanes joins the city with Yucatán's biggest port city, Progreso.

- Mérida-Umán-Campeche (Federal 180) connects with the city of San Francisco de Campeche.

- Mérida-Kantunil-Cancún (Federal 180), a four-lane road that becomes a toll road at Kantunil, joins Mérida with Chichén Itzá, Valladolid and ultimately Cancún.

- Mérida-Tizimín (Federal 176) connects Mérida with Tizimín (the second largest city in Yucatán).

- Mérida-Teabo-Peto, known as Mundo Maya Road Carretera del Mundo Maya, is used in both "convent route" Ruta de los Conventos and as a link to the ancient Maya city of Mayapán and Chetumal, state capital of Quintana Roo.

Health

[edit]

Mérida has many regional hospitals and medical centers. All of them offer full services for the city, and in case of the regional hospitals, for the whole Yucatán peninsula and neighboring states.

The city has one of the more prestigious medical faculties in Mexico (UADY). Proximity to American cities like Houston allow local doctors to crosstrain and practice in both countries making Mérida one of the best cities in Mexico in terms of health services availability.

Hospitals:

- Public:

- Hospital Regional del ISSSTE

- Hospital Ignacio García Téllez Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS)

- Hospital Benito Juárez IMSS

- Hospital Agustin O'Horán

- Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad

- Private:

- Clínica de Mérida

- Star Médica

- Centro Médico de las Américas (CMA)

- Centro de Especialidades Médicas

- Hospital Santelena

- Centro Médico Pensiones (CMP)

- Hospital Faro Del Mayab

Education

[edit]

In 2000, the Mérida municipality had 244 preschool institutions, 395 elementary, 136 Jr. high school (2 years middle school, 1 high), 97 High Schools and 16 Universities/Higher Education schools. Mérida has consistently held the status of having the best performing public schools in Mexico since 1996. The public school system is regulated by the Secretariat of Public Instruction.[39] Attendance is required for all students in the educational system from age 6 up to age 15.[39] Once students reach high school, they are given the option of continuing their education or not; if they chose to do so they are given two tracks in which they can graduate.[39]

Nevertheless, education in Merida has a variety of quality throughout the city. This mainly has to do with the different social strata and where they reside. Mayan indigenous population are at the bottom of the spectrum and this can be represented in the type of education that the children are receiving. Upper class is usually located in the north, as it is less populated and has higher living costs.[40] For the most part, private schools are located in the northern part of the city. The only students who attend these schools are those of high class and of non-Maya descent.[41] A distressing statistic of how this affects the indigenous communities can be noted, "In Yucatan only 8.9 % of the Mayans have achieved junior high and solely the 6.6% have studied beyond that point. The 83.4% of the Mayans 15 years old and older dropped out of school before finishing junior high."[42]

Many laws have been set in place to avoid discrimination between the Spanish speakers and the Mayan speakers as the "Law says that it is a duty of the Mexican State to guarantee – guarantee, not just try, not just attempt – that the indigenous population has access to the obligatory education, bilingual and intercultural in their methods and contents."[42] Despite this having been set into law, there is no bilingual or cultural accepting program after elementary school.[42] The system for indigenous education only serves about one third of the Mayan speaking population of the area.[42] Many Maya[43] children are forced to learn Spanish and cease using their native tongue, which may be challenging for them to do. This in turn causes many of the students to feel that learning at school is not their strong suit and may even end up dropping out early in their education.[42]

There are several state institutions offering higher education:

- Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY)

- Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana (UTM)

- Instituto Tecnológico de Mérida (ITM)

- Escuela Superior de Artes de Yucatán (ESAY)

- Universidad Pedagógica Nacional

- Escuela Normal Superior de Yucatán (ENSY)

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Merida satellite campus (UNAM)

- Universidad Politécnica de Yucatán (UPY)

Among several private institutions:

- Centro de Estudios Superiores CTM (CESCTM)

- Colegio de Negocios Internacionales (CNI)

- Universidad Anáhuac Mayab

- Universidad Marista

- Centro de Estudios Universitarios del Mayab (CEUM)

- Universidad Modelo

- Universidad Interamericana para el Desarrollo (UNID)

- Centro Educativo Latino (CEL)

- Universidad Interamericana del Norte

- Centro Universitario Interamericano(Inter)

- Universidad Mesoamericana de San Agustin (UMSA)

- Centro de Estudios de las Américas, A.C. (CELA)

- Universidad del Valle de Mexico (UVM)

- Instituto de Ciencias Sociales de Mérida (ICSMAC)

- Universidad Popular Autónoma de Puebla, Plantel Mérida (UPAEP Mérida)

Mérida has several national research centers. Among them

- Centro de Investigacíón Científica de Yucatán (CICY)

- Centro de Investigaciones Regionales Dr. Hideyo Noguchi, dependent from the UADY, conducts biological and biomedical research.

- Centro INAH Yucatán, dedicated to anthropological, archaeological and historic research.

- Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados CINVESTAV/IPN

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Merida, Mexico Metro Area Population 1950–2022". macrotrends. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "TelluBase—Mexico Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ INEGI. "Archivo Histórico de Localidades. Mérida" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ "Diccionario Maya-Español". Yucatán: Identidad y Cultura Maya. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ "Mérida en la region de Yucatán – Municipio y presidencia municipal de México – presidencia municipal México – Información presidencia municipal, ciudades y pueblos de México". www.los-municipios.mx. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Roller, Sarah (November 20, 2022). "Mérida Cathedral – History and Facts". History Hit. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "Centro Histórico Mérida – Mérida Mexico Real Estate". Property Pros Mx Real Estate. February 22, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ Poling, Monica (January 25, 2016). "Merida Chosen American Capital of Culture 2017". Travel Pulse Canada. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "Down Mérida way: homebuyers flock to Mexico's safest city". Financial Times. April 12, 2022. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "Merida ISCCC". International Safe Community Certifying Centre. 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Durán, Guadalupe (2016). "Merida Tops Forbes List of Best Cities in Mexico". Top Mexico Real Estate. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "Study by UN-Habitat, Infonavit ranks Mérida No. 1 for quality of life". Mexico News Daily. November 10, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "Earth from Space: Mexico's 'White City'". European Space Agency. May 4, 2006. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "¿Qué significa Arequipa, nombre de la 'Ciudad Blanca' del Perú?". infobae (in European Spanish). August 6, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ Romoleroux, Michell Francois (January 6, 2022). "¿Por qué a Popayán le dicen la Ciudad Blanca?". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ Adams, Robert (April 30, 2018). "Mérida History: The 'White City' and its colonial arches". Punto Medio. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Arcos de Mérida" (in Spanish). Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ Bracamonte y Sosa, Pedro (2006). La perpetua reducción. Documentos sobre la huída de los mayas yucatecos durante la colonia [The Perpetual Reduction. Documents on the flight of the Yucatec Mayas during the colony] (in Spanish). Centro de Investigación y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. p. 222. ISBN 958-456-594-X.

- ^ . . Vol. III. 1914. p. 1207.

- ^ Fodor's 2001 Cancún, Cozumel, Yucatán Peninsula p.167. Fodor's, 2000

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ "Estado de Yucatán-Estacion: Mérida Centro". Normales Climatologicas 1951–2010 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorologico Nacional. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1981–2000" (PDF) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "Merida Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Yucatan economy growth three times higher than the national average". The Yucatan Times. November 6, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Mérida – Mexico". World Bank Group. September 20, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Walsh, Nora. "A Guide To Merida, Mexico: 10 Reasons To Visit Now". Forbes. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Merida English Library". Merida English Library. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "The Yucatan Symphony Orchestra". Osy.org.mx. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Sima Lorenzo, Eyder Gabriel (August 9, 2013). "Actitudes de Yucatecos Bilingues de Maya y Español Hacia la Lengua Maya y sis Hablantes en Merida Yucatan". Estudios de Cultura Maya.

- ^ "The Camara Brothers' Twin Houses". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ Dickerson, Marla (October 21, 2007). "Paradise for home remodelers – Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "Marathon Mérida BaNorte". Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Carlos Rosado van der Gracht (November 22, 2023). "Mérida New Va y Ven Transit Network is a Huge Step in the Right Direction". Yucatán Magazine.

- ^ "Yucatán estrenará en 2023, IE-TRAM, transporte público 100% eléctrico". energy21.com.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ "Tráfico de Pasajeros | Tráfico de Pasajeros". www.asur.com.mx. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Tribuna del Yaqui". tribuna.com.mx. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016.

- ^ "El 15 de diciembre inicia ruta Palenque-Cancún; todos los tramos, para febrero: AMLO". sinembargo.mx (in Spanish). October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Mérida Education – Expats In Mexico". Expats in Mexico. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Programa Integral de Desarrollo Metropolitano PIDEM (PDF).

- ^ Azcorra, Hugo (2013). "Nutritional Status of Maya Children, Their Mothers, and Their GrandmothersResiding in the City of Merida, Mexico: Revisiting the Leg-Length Hypothesis". American Journal of Human Biology. 25 (5): 659–65. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22427. PMID 23907793. S2CID 205302992.

- ^ a b c d e Mijangos-Noh, Juan Carlos (April 14, 2009). Racism Against the Mayan Population in Yucatan, Mexico: How Current Education Contradicts the Law (PDF). Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

- ^ Livingston, Eric. "Cities in Mexico and Brief History". Latam Living.