Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

The Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904, known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since the voyage of James Clark Ross sixty years earlier (1839–1843). Organized on a large scale under a joint committee of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), the new expedition carried out scientific research and geographical exploration in what was then largely an untouched continent. It launched the Antarctic careers of many who would become leading figures in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, including Robert Falcon Scott who led the expedition, Ernest Shackleton, Edward Wilson, Frank Wild, Tom Crean and William Lashly.

Its scientific results covered extensive ground in biology, zoology, geology, meteorology and magnetism. The expedition discovered the existence of the only snow-free Antarctic valleys, which contains the longest river of Antarctica. Further achievements included the discoveries of the Cape Crozier emperor penguin colony, King Edward VII Land, and the Polar Plateau (via the western mountains route) on which the South Pole is located. The expedition tried to reach the South Pole travelling as far as the Farthest South mark at a reported 82°17′S. (Full article...)

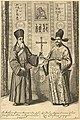

Selected image

1675 image of a Chinese astronomer with an elaborate armillary sphere. In the 17th century, Chinese astronomers collaborated extensively with Jesuit scholars, who brought the Copernican and Tychonic systems from Europe.

Did you know

... that the Merton Thesis—an argument connecting Protestant pietism with the rise of experimental science—dates back to Robert K. Merton's 1938 doctoral dissertation, which launched the historical sociology of science?

...that a number of scientific disciplines, such as computer science and seismology, emerged because of military funding?

...that the principle of conservation of energy was formulated independently by at least 12 individuals between 1830 and 1850?

Selected Biography -

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, AC, KBE, FRS, FAA, FTSE (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapons.

Born and raised in Adelaide, South Australia, Oliphant graduated from the University of Adelaide in 1922. He was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship in 1927 on the strength of the research he had done on mercury, and went to England, where he studied under Sir Ernest Rutherford at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory. There, he used a particle accelerator to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei (deuterons) at various targets. He discovered the respective nuclei of helium-3 (helions) and of tritium (tritons). He also discovered that when they reacted with each other, the particles that were released had far more energy than they started with. Energy had been liberated from inside the nucleus, and he realised that this was a result of nuclear fusion. (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1602 – Birth of Otto von Guericke, German physicist (d. 1686)

- 1704 – Death of Charles Plumier, French botanist (b. 1646)

- 1764 – Death of Christian Goldbach, Prussian mathematician (b. 1690)

- 1778 – Death of Francesco Cetti, Italian Jesuit scientist (b. 1726)

- 1841 – Birth of Victor D'Hondt, Belgian mathematician (d. 1901)

- 1856 – Death of Farkas Bolyai, Hungarian mathematician (b. 1775)

- 1877 – Thomas Edison announces his invention of the phonograph, a machine that can record and play sound

- 1886 – Birth of Karl von Frisch, Austrian zoologist, Nobel laureate (d. 1982)

- 1889 – Birth of Edwin Hubble, American astronomer (d. 1953)

- 1905 – Albert Einstein's paper, Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?, is published in the journal "Annalen der Physik". This paper reveals the relationship between energy and mass. This leads to the mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc²

- 1908 – Death of Georgy Voronoy, Russian mathematician (b. 1868)

- 1910 – Birth of Willem Jacob van Stockum, Dutch physicist (d. 1944)

- 1945 – Death of Francis William Aston, British chemist, Nobel laureate (b. 1877)

- 1953 – The British Natural History Museum announces that the "Piltdown Man" skull, initially believed to be one of the most important fossilized hominid skulls ever found, is a hoax

- 1963 – Birth of Timothy Gowers, British mathematician

- 1976 – Death of Trofim Lysenko, Russian biologist (b. 1898)

- 2006 – Death of Zoia Ceauşescu, Romanian mathematician (b. 1950)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus